CAROTENOIDS

Carotenoid, pronounced like a cross between a martial arts form (karate) and a humanoid, USUALLY produces red, yellow, and orange feather colors. You can recognize these pigments as the orange in carrots, yellow in corn, and the red of a lobster or orange in orioles, yellow in goldfinches, red in cardinals and Summer Tanagers. These colorful pigments are made by plants or critters that eat the plants and then ingested by animals.

In part one, you learned that melanin production forms during feather formation. Carotenoids also are deposited during feather formation in the follicle. In addition to depositing the colorful pigments from their diet, many species can chemically modify them on how much and where they are deposited. At least 600 or 1100 different carotenoids have been identified according to several studies. Plus they can interact with other pigments such as melanin to produce an olive-green color. Trying to ferret out the origin of specific colors is difficult.

In the past, feather pigment research processes destroyed feathers. Now with a fancy spectrograph, analyses can be performed from living and even extinct species without pulverizing plumage. With new data, older theories are questioned. Prior to spectrography, scientists believed that dietary carotenoids gave an “honest signal” of the bird’s health and vitality. Even as humans we’ve heard about the benefits of carotenoids in our diets as antioxidants and immune boosters. Couldn’t this happen in birds as well?

But then the real McCoy enters with her recent research in 2020 of males and females of nine tanager Ramphocelus species. Both sexes have plumage colors from carotenoids but females sport drab feathers while intense colors adorn the males. One species, the Silver-beaked Tanager, I happened to photograph in Peru. Note the vibrancy of the male plumage:

Ms. McCoy learned that both sexes of each of the nine species contained the same amount of pigments in the same concentration. Going beyond the spectroscope, she used electron microscopy to differentiate the look of the barbs and barbules. Males had a fuzzy look due to wider or oblong barbs and strap-shaped or angled barbules. These micro feather parts reflected less light to produce dark velvety feathers.

Meanwhile female feathers laid flatter and in a single plane of both tube-shaped barbs and barbules. These microstructures are the difference between the light and dark redness. Just like birds don’t have blue pigments, which will be discussed in part 3, and my idea for the title, “Pigments of Imagination,” the colors in these tanagers illustrate an optical illusion. So carotenoids can also be pigments of imagination!

Although carotenoids produce yellow colors, yellow plumage in penguins appears to develop from spheniscin, a unique class of pigments only manufactured by penguins, not by diet.

At this point, I’m hesitant to introduce another set of pigments, porphyrins, due to more conflicting data, but here goes. Remember many pigments and/or the structure of the plumage impact the colors we see.

PORPHYRINS, OWLS THAT GLOW, & VIRGINITY SIGNALS

Our third pigment group, porphyrins, pronounced like “por friends,” act like some friends that become best friends forever (BFFs) or other friends that disappear quickly. Some are permanent pigments and others aren’t. Although the name may seem odd, in reality you should celebrate the iron-containing porphyrin, heme, which is in hemoglobin in your blood and it’s also in your green veggies as the base for chlorophyll!

In birds porphyrins produce colors like pinks and browns in the lighter colored feathers in most owls, pigeons, nightjars, bustards (careful with this name), certain game birds, like grouse, and domestic fowl (gallinaceous species).

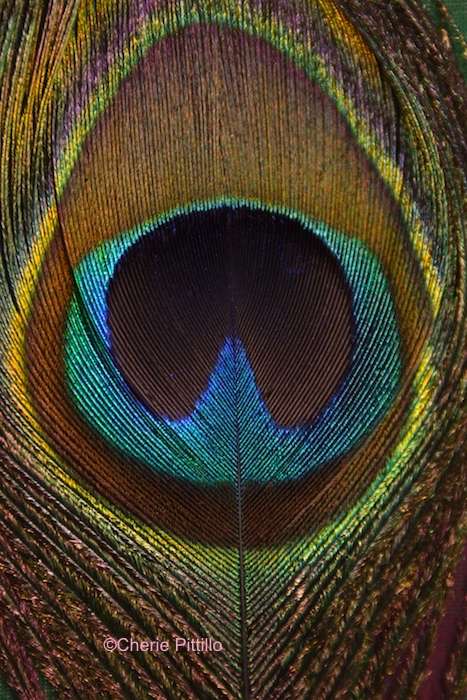

Note the pink feathers of the Indian Peacock in the first image. Also porphyrins create the bright reds and greens of an African bird group called turacos, as well as some galliforms, ducks, and jacanas. They even may add color to egg shells.

A spectacular trait of porphyrins is they glow (fluoresce) when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light! However they degrade in light and seem to be more common in new feathers along flanks, downy feathers, or undersides of wings of certain birds. Researchers indicate how the age of owls could be determined by the amount of pink that glows under black UV light.

This information confuses me. Owls don’t have UV vision because they lack the cones (color receptors) in their eyes for UV vision. However, their rods (light receptors) increase in sensitivity to detect brighter UV feathers at night!

But wait, there is more about porphyrins.

Bustards, found in Eurasia, Africa, and Australia, are mid-to-large ground birds. During breeding season, males perform in a group, called a lek, in front of females. (Shouldn’t that be called a lechery?) These elaborate displays of the males expose pink colors found at the base of several feathers, which are usually hidden. The performance seems to enhance a female to get close to the male to check out that coloration.

Remember that porphyrins fade when exposed to light? In two different bustard species, the color disappeared in 12 minutes with one and in 25 minutes in another. Unlike most permanent porphyrin pigments, these are fleeting (ephemeral) in certain species.

Apparently, a female bustard may select a male with the most vibrant pink colors which suggests the male just arrived at the lechery, uh, lek, to perform his first displays. It could serve as a sign of virginity and therefore readiness for first mating. Researchers theorize the more a male mated with several females, the more his pink color faded during his displays and his sperm quality reduced with each mating.

I’ll leave you with one more owl image photographed in the daytime. *Brown colors of the Great Horned Owl are produced by melanin. Flanks of this species glow pink under UV light due to porphyrins. And the yellow eyes can be due to pterins, a pigment found in all living organisms including butterflies, reptiles, and amphibians, but not so much in birds. However, some bird-eye colors are from pterins or purines, or carotenoids.

Confused? Wait until you read part 3 next month about exclusive parrot pigments and that blue feathers aren’t blue.

CELEBRATE NATURE IN EVERY COLOR REGARDLESS OF THEIR ORIGIN!

* Link to Part 1 https://www.theyucatantimes.com/2021/08/backyard-birding-in-merida-yucatan-and-beyond-pigments-of-your-imagination-bird-plumage-part-1-of-3/

DISCLAIMER: References do not agree about this information.

Sal a Pajarear Yucatán, Birds & Reserves of the Yucatan Peninsula, A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and North Central America, The Handbook of Bird Biology, A Dictionary of Birds, The Sibley Guide to Birds, What It’s Like To Be A Bird

https://www.nature.com/articles/srep39210

https://www.audubon.org/news/what-makes-bird-feathers-so-colorfully-fabulous

https://www.chattanoogan.com/2008/4/18/126125/Ask-the-Naturalist–How-do-Birds-get.aspx

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29436755/

https://www.dictionary.com/browse/lechery

www.nature.com/articls/srep39210

https://nanopdf.com/download/feather-color-i_pdf

https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/molecule-of-the-week/archive/c/chlorophyll.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1626226/

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/02/090213114154.htm

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2394316/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4848976/

https://www.britannica.com/science/coloration-biology/Indole-pigments

https://www.audubon.org/news/what-makes-bird-feathers-so-colorfully-fabulous

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29311592/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2394316/

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-02649-z

https://www.britannica.com/science/coloration-biology/Nitrogenous-pigments

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30825468/

https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article/26/1/158/2261730

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsif.2012.1065

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1600-0749.1987.tb00401

https://www.sciencedirect.com/sdfe/pdf/download/eid/3-s2.0-B0124437109005597/first-page-pdf

Cherie Pittillo, “nature-inspired,” photographer and author, explores nature everywhere she goes. She’s identified 56 bird species in her Merida, Yucatan backyard view. Her monthly column features anecdotes about birding in Merida, Yucatan and also wildlife beyond the Yucatan.

Contact: [email protected] All rights reserved, ©Cherie Pittillo