This is an excerpt from an article originally published in “Religious News Service”. Author Andrew Chesnut is a professor of religious studies and holds the Bishop Walter F. Sullivan Chair in Catholic Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Mexicans will tell you 90 percent of them are Catholic, but 100 percent are Guadalupan.

While the proportion of Catholics in Mexico isn’t accurate anymore, the Virgin of Guadalupe remains a cherished part of Mexican national identity, reflected in the fact that millions of women and men are named Guadalupe, many going by the nickname “Lupe or Lupita.”

La Virgen Morena (the Brown Virgin) is not only patroness of Mexico but also Empress of the Americas, from Chile to Canada. While other manifestations of Mary claim at most a region or country, Guadalupe is the only one to reign over two continents.

These are 10 fascinating facts about the Virgin who led Mexicans to independence from Spain:

1.) Many Mexicans aren’t aware the original Guadalupe is from Extremadura, Spain.

In fact, Christopher Columbus was a devotee and even named the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe in her honor, after she purportedly saved his fleet from a storm at sea. The Spanish Guadalupe is one of several black European virgins, so in her Mexican incarnation she actually became lighter-complexioned as the Virgen Morena.

The Aztec goddess’s name, Tonantzin, means “Our Mother” in the Aztec language of Nahuatl, so some skeptics contend that the Spanish colonial church concocted the story of Guadalupe appearing to Juan Diego as a way to convert his fellow Aztecs and other indigenous groups to Christianity.

3.) Despite his canonization in 2002, there is no hard evidence St. Juan Diego ever existed.

At the time of the controversial canonization, the abbot of the basilica, Guillermo Schulenberg, resigned, claiming that Juan Diego had never existed and “is only a symbol.” The Aztec peasant was canonized, nonetheless, as part of a strategy to retain indigenous Catholics in Mexico and across Latin America who have been defecting in droves to Protestantism, especially Pentecostalism.

Perhaps the most spectacular miracle, according to devotees, is the tilma emerging unscrathed from a bomb blast. A metal crucifix resulted damaged instead, and it has been worshipped ever since as “El Cristo del Atentado” (The Christ of the attack).

(Photo: Google)

4.) Art historians have discovered that depictions of the Virgin’s skin color have become progressively darker.

Studies on her historical development, such as those by historian Stafford Poole, demonstrate that contrary to legend, it was Mexican creoles (people of Spanish descent born in Mexico), and not indigenous converts, who were the first devotees of Guadalupe and the primary propagators of her cult.

Artistic renditions of Guadalupe became noticeably darker on the heels of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20), which led to the exaltation of the mixed-race mestizo as the new model of Mexicanness.

5.) Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1810 transformed her into the national patroness.

6.) La Morena remained relatively unchanged in artistic renditions until as recently as the 1980s.

The first artists to experiment with novel depictions of the Empress of the Americas were Mexican-Americans who didn’t feel as culturally and religiously constrained as their Mexican counterparts in exploring new ways of representing her, using all kinds of media.

A bare-breasted Guadalupe created by artist Paz Winshtein was the object of considerable controversy when it was displayed at a gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 2014.

A pilgrim holds up an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe at the Basilica of Guadalupe during an annual pilgrimage in honor of the Virgin, the patron saint of Mexican Catholics, in Mexico City, Mexico on Dec. 12, 2015. Photo courtesy of Reuters/Henry Romero

7.) The etymology of her name is the subject of considerable debate.

Some linguists and historians point to Nahuatl origins, while others, more convincingly, remind us that the name “Guadalupe” already existed in Spain, and thus we should look there for its etymological genesis. There is little doubt that the prefix “Guada” comes from the Arabic “wadi,” or river valley. The jury, however, remains out on “lupe,” which many assert comes from the Spanish “lobo” (“lupus” in Latin), or wolf.

8.) Guadalupe was an integral part of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20).

Fighting under the slogan “land and liberty,” revolutionary peasant leader Emiliano Zapata and his fighters carried the Mestiza Virgin on banners into battle against Mexican oligarchs. Some Zapatista guerrillas carried on the tradition during their uprising in 1994 in the southern state of Chiapas.

9.) In 1929, the official photographer of the basilica discovered an image of a bearded man in her right eye.

Two decades later another “expert” not only confirmed the presence of the original bearded man but also claimed to see it in both her eyes. Since then, the “secret of her eyes” has expanded to include images of an entire family supposedly visible in both of her pupils. For believers, the images are reflections of what Guadalupe saw when she appeared almost five centuries ago to St. Juan Diego.

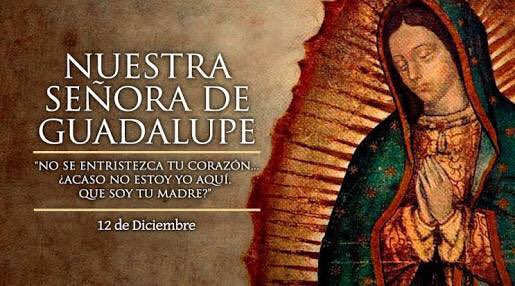

“Don’t let your heart grieve… Ain’t I here as your mother?” Words of Our Lady of Guadalupe to Juan Diego (Image: Google)

10.) The tilma upon which the Virgin’s image is imprinted is held to be miraculous by devotees.

Some scientists claim an absence of brush strokes on the cloak, while others report that the coloration contains no animal or mineral elements. Perhaps the most spectacular miracle, according to devotees, is the tilma emerging unscathed from a bomb blast.

In 1921 an anti-clerical radical detonated 29 sticks of dynamite in a pot of roses beneath the cloak. The blast destroyed a marble rail, twisted a metal crucifix, and shattered windows throughout the old basilica — but the tilma itself was untouched.

Source: http://religionnews.com/