With a little more than six weeks before Donald Trump takes over with an agenda that could batter Latin America’s second-largest economy, Mexico is already showing signs of strain. Inflation is bouncing back, and traders bet it will only get worse; the peso has plummeted to record lows, and top analysts predict more pain; the government has lowered its growth forecast for four straight years, and Mexico is on the verge of a credit-rating cut just as Agustin Carstens gears up to leave the central bank after seven years at the helm.

While no one is calling for a full-blown crisis yet, there’s plenty of concern that returns could be subpar for months or even years to come as peso volatility increases. If this were a smaller developing nation it probably wouldn’t matter for your pension fund. Even Brazil — the region’s largest economy — isn’t nearly as integrated into international markets. But foreign investors such as Janus Capital Group Inc. and Pimco hold $140 billion of Mexico’s local-currency government debt, the most for any emerging market based on World Bank data, and the peso is among the world’s most widely held currencies.

“There is a bit of a delicate situation at the moment,” said Alvise Marino, a foreign-exchange strategist at Credit Suisse Group AG who has the most bearish forecast for the peso next year, predicting it will sink 16 percent by the end of September after tumbling 15 percent this year. “Everybody’s talking about the risk of the peso.”

“A broad stability of the peso is a global public good,” said Alberto Ramos, the chief Latin America economist for Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in New York. “It has repercussions and implications across the financial system and even areas of the financial system that are not directly related to Mexico.”

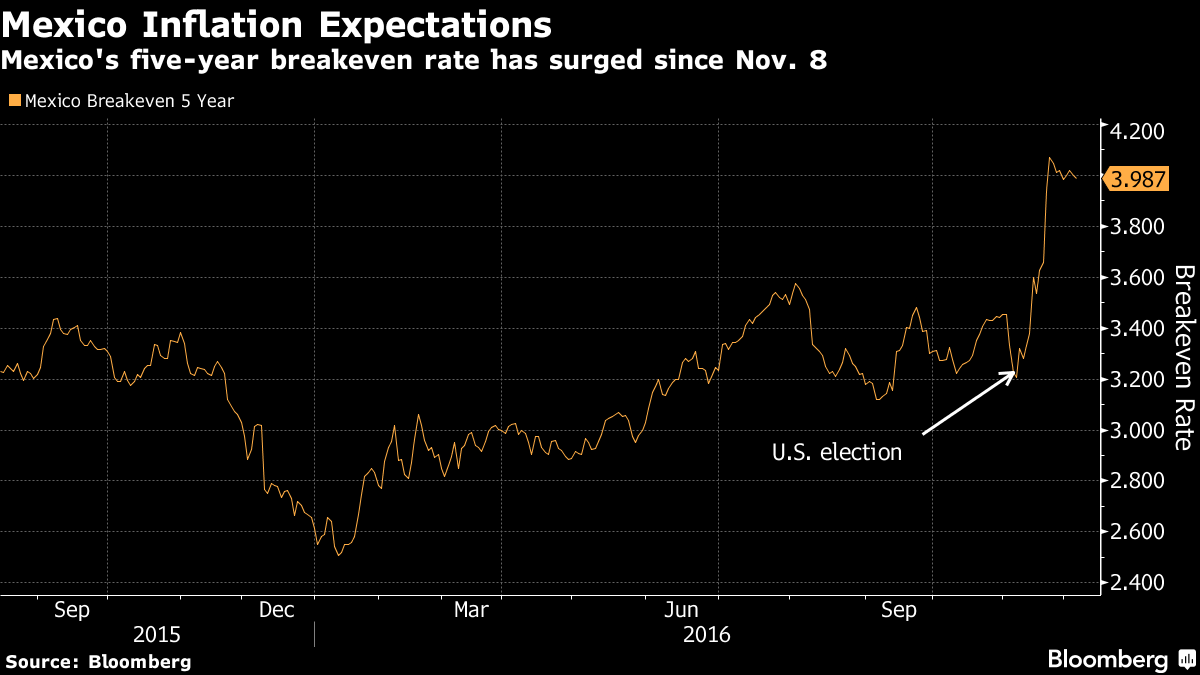

Among the biggest concerns for investors is inflation, especially as Carstens plans to leave the central bank in July to join the Bank for International Settlements. The five-year breakeven rate, a bond market measure for cost-of-living expectations, has climbed to 4 percent from 3.2 percent before the U.S. election. November’s reading was the highest in almost two years, and Citigroup Inc. expects prices to increase 4.8 percent next year, the most since 2008.

Even if Mexico gets a handle on inflation and none of Trump’s threats come to pass, there’s still the risk peso investors will be punished by broader concern about emerging markets. The currency has long been used as a proxy to hedge risk in less-liquid markets, according to Gabriel Casillas, the head of research in Mexico City at Grupo Financiero Banorte SAB.