Xuchiles are funeral offerings in the form of flowers and cacti about two meters wide and the height of a story and half building. They are intricate to the Chichimeca (indigenous hunter gatherers) celebrations of the town’s namesake, St. Michael the Archangel’s, feast day here.

The construction of a xuchil requires great skill. First the sticks are tied in a parallel fashion in order to form a rectangle. Upon this skeleton structure of reeds are mounted squares about ten inches on each side covered with a matting woven of a plant called little spoon because of the shape of its leaves. In each xuchil three of four of these squares are left empty. Within the vacant squares are placed flower arrangements, saints, Virgins, crosses and other motifs. All the arrangements are partially made of dyed tortillas, sun flowers, marigolds and passion flowers.

Marigolds, and cacti parts placed together to represent marigolds, are a nod to the odd smell of the now blooming wild marigolds. Their odor was part of what brought the dead back for Days of the Dead with each flower’s 365 petals representing a day in the year of a good life. To the Spanish, the gold color represented gold from Mary’s dowry and why we call the flower, marigolds.

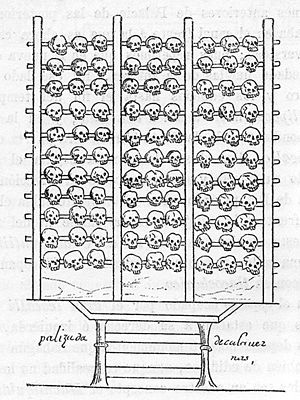

The little spoon cacti are white, representing skulls woven together into a tzompantli, or skull rack, used in Pre-Hispanic time. A tzompantli was used for the public display of skulls of war captives and other sacrificial victims.

At the top of each xuchil appears a handsome woven cross representative of the cross that appeared in the sky ending the 1530 Battle of the Barbarians between the indigenous and Conquistadors on St. Michael’s day. Hence, the town’s name became San Miguel (then San Miguel de los Chichimecas and today San Miguel de Allende).

Alongside the xuchil’s cross are often two smaller crosses. They are not for St. Dimas and Gespas, the lads crucified alongside Jesus. Rather these crosses represent Wolf and Coyote, two fierce Chichimeca warriors from the nearby Battle of the Barbarians in 1530. Restricted from being in the procession in 1960 by a priest not partial to the notion of two men that fought the Catholics were being honored. In recent years I’ve seen Wolf and Coyote creep back into the celebrations.

Hearts are displayed on many xuchils representing the sacred heart of Jesus, a European image to show Jesus’ compassion via his exposed heart. Before the arrival of the Spanish the highest indigenous leader got to eat the heart of prisoners of war, so the power of the heart was already part of the culture. Today San Miguel is the Heart of Mexico for the revolution from Spain starting here and being Mexico’s most romantic city for being built upon pink quartz. The quartz is why we don’t suffer earthquakes, unless you are out by the lake as the tremors travel in the water.

Borders on a xuchil’s block represent the duality of life, or how one must be born, and die, to go on home to Jesus in Heaven.

An X signifies the four winds (north, south, east and west) the indigenous face when spreading a prayer out into the world.

Each group of Chichimeca dancers escorting a xuchil includes men, women and children creating the sign of the cross with their feet to thank their ancestors for joining the new faith. In the group are persons who made religious vows to make the pilgrimage to town and who have taught the dancers. Amateurs need not apply nor are strangers permitted to disturb the dignity, unity and discipline of the group. Costumes are often warlike and highly individualized. They frighten me, a tall present-day man. I can only imagine the reaction from those tiny Spanish folk that arrived so long ago.

Groups are often led by two elders, a man in white cotton trousers and a woman (or younger folks dressed as senior citizens). They represent the ancient gods of astrology and calendars, Cipactonal (him) and Oxomoco (her). They were the first human couple, like a New World version of Adam and Eve. Today Oxxo’s are a chain of convenience stores.

Interspersed in the procession are the clowns, skeletons and other locos (crazies) plus the devil with his ever-present whip to keep participants submissive.

Following a four hour procession in honor of St. Michael, the xuchiles are placed in the front of the Parroquia symbolically bringing the ancestors back to their tombs because St. Michael’s church was build atop the Chichimeca graveyard. The Spanish always built churches where the indigenous were already use to worshipping (in much the same way pyramids were destroyed with their stones used to build a church).

Before leaving town, the dancers have food blessed by the priests and brought to the prison. The xuchiles are left behind to silently decay. You can view theirs, and other xuchil remains alongside churches and cemeteries throughout town following their continued use in today’s funeral processions.

by Joseph Toone

- TripAdvisor’s top tour guide in San Miguel de Allende with History and Culture Walking Tours and Joseph Toone Tours.

- Amazon’s best selling author of the San Miguel de Allende’s Secrets book series on history, holidays, tours and living in San Miguel.

1 comment

Having read this I believed it was rather informative. I appreciate you taking the time and effort to put this informative article together. I once again find myself personally spending a lot of time both reading and commenting. But so what, it was still worth it!

Comments are closed.