APASEO EL ALTO, Guanajuato, Mexico (Reuters) – After her husband was shot dead while running for mayor of Apaseo el Alto in central Mexico in 2018, Maria del Carmen Ortiz took over his campaign and, pushing through her grief, won the vote after becoming a symbol of residents’ hunger for justice.

A year and a half after taking office, Ortiz must now be accompanied by three police bodyguards wherever she goes, as her home state of Guanajuato has emerged as the most murderous in Mexico, caught in a battle between rival criminal cartels.

Three town officials have been killed during her tenure: her transit director, tax chief and a city councilor. Like her husband’s killing, none of their murders have been solved.

Now Ortiz is using her position as mayor to call for thorough investigations by prosecutors of their killings and dozens more in the hilly town.

“They file the cases away,” Ortiz, 34, said in her office at the two-story municipal palace beside photos of her late husband Jose Remedios Aguirre, who was 35 when he died, and their three children. “They should do their job, but do it well, so there’s justice: for my husband, for my colleagues, for everyone.”

The streets of Apaseo el Alto, home to some 70,000 people, are narrow yet bustling, lined with mom-and-pop businesses and dollar exchange stores serving locals with family members who bring earnings back from the United States.

According to federal government data, the number of killings jumped here to 87 last year from 10 in 2015.

The local records, kept at the fenced-in police station on the outskirts of town, paint an even grislier picture: 120 murders last year and none of them solved.

A security crisis inherited by President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has worsened in many parts of Mexico since he took office in December 2018, as he eased back on a war against the cartels and pledged instead to tackle what he calls the root causes of violence: corruption, poverty and lack of opportunities for young people.

On his watch, Mexico tallied a record of 34,582 murders last year. Yet experts say Mexico’s justice system is ill-equipped to solve them, feeding a vicious cycle of impunity and crime.

Ortiz backs Lopez Obrador’s policy. She decided to run for office after he endorsed her at his campaign rally in Apaseo el Alto, lifting her hand into the air. Onlookers applauded and broke into chants of “Justice! Justice!”

Yet Guanajuato opened a record 2,775 murder investigations last year, making it the bloodiest state in Mexico. A decade ago, the state – home to nearly 6 million people – had just 437 murders.

Security consultants say the jump in killings is tied to a battle between Guanajuato’s Santa Rosa de Lima gang and its bigger rival, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) from neighboring Jalisco state.

In Guanajuato, just 10.5% of homicides under investigation result in jail time, according to a 2018 study from the University of the Americas Puebla. For Mexico as a whole, the figure is little better at 17%.

Many blame the entrenched impunity on an overwhelmed justice system in which the police, prosecutors and judges lack the training to prosecute crimes successfully, and where corruption and political interests derail investigations.

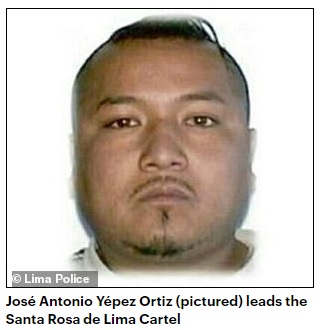

Experts say, moreover, that criminal groups target local officials to deter investigations into their activities. They believe Santa Rosa is likely behind various political assassinations in the area, including in Apaseo el Alto, which is just 25 miles (40 km) from the gang’s birthplace.

However, the town’s public security minister Jose Abraham Dominguez said he had not identified any organized crime group in the municipality. He said that violence could be spilling over from gangs in neighboring states.

“Perhaps they come, they pass through, but we don’t have any criminal group here,” he said.

GANG WAR

In the wake of the fragmentation of many criminal groups, the Jalisco cartel has made a push to claim swathes of territory throughout Mexico, driving up murder levels across the country as other groups band together against it.

“They’re waging all out war,” said Falko Ernst, a senior analyst at International Crisis Group. “There are resources pouring in on both sides sustaining bloodshed for the foreseeable future.”

According to Sophia Huett, Guanajuato’s security commissioner, 85% of homicides carried out in the state are tied to organized crime.

Fighting among criminal groups has worsened in the past year since Lopez Obrador’s administration cracked down on fuel theft from pipelines owned by state oil company Pemex, said Huett: “Because there’s less product, the fight becomes bloodier, more violent.”

Worth up to an estimated $3 billion a year nationally before the government intervention, the revenues from fuel theft boosted Santa Rosa’s rise – and are coveted by the CJNG, whose own rise built on drug trafficking.

With one-third of Pemex’s pipelines running through Guanajuato, the state has become a battleground for control of the illicit trade.

CJNG can afford to quickly send in new recruits given its presence not only in Jalisco, but in other nearby states.

“They work as a franchise,” Huett said. “You have two people from the Jalisco cartel here one day, and the next day, they send another two.”

As a newcomer in Guanajuato, the Jalisco cartel has struggled to match Santa Rosa’s homegrown roots and the help it receives from local criminals and officials.

Instead, it must rely on firepower.

“They are going to fight inch by inch throughout the country, not through community support, but with violence and economic power,” said security consultant Juan Miguel Alcantara, who was deputy attorney general in former president Felipe Calderon’s government.

For Alcantara, a lack of resolve by Lopez Obrador’s government has encouraged cartels in Guanajuato to act more brazenly due to a sense of impunity.

At least twice last month alone, gunmen in a part of Guanajuato dominated by Santa Rosa blocked highways with burning cars and shot at police, raising questions of whether the gang’s notoriously violent leader, Jose “El Marro” Yepez, was retaliating against authorities closing in on him and family members.

The incidents paralyzed parts of Guanajuato for hours, reminiscent of the Sinaloa cartel’s show of firepower when it sent gunmen to storm the northern city of Culiacan last year, forcing outnumbered security forces to free the son of Sinaloa capo Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, who had been captured hours before.

Lopez Obrador said after the incident in Culiacan it was more important to prevent mass civilian deaths.

“They saw that in Sinaloa it worked… so they’re trying the same thing here,” Alcantara said. “They know the same thing will happen: that the authorities are going to cave in.”

(Reporting by Daina Beth Solomon; Editing by Daniel Flynn and Alistair Bell for Reuters)

Source: Reuters