What do Nelson Rockefeller, Madonna, Frida, Diego and countless others have artistically in common? An interest in the burgeoning appeal of collecting Mexican retablos for both their artistic value and expressions of a faith-based culture.

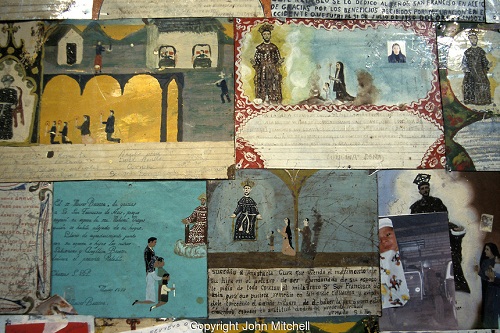

Retablos thanking Saint Francis of Assisi for miracles in the Templo de la Purisima Concepcion, the parish church or parroquia in the 19th-century mining town of Real de Catorce, Mexico. Real de Catorce became a virtual ghost town during the early part of the 20th century. It has recently become a popuar destination for travellers. It is also a Catholic pilgrimage site.

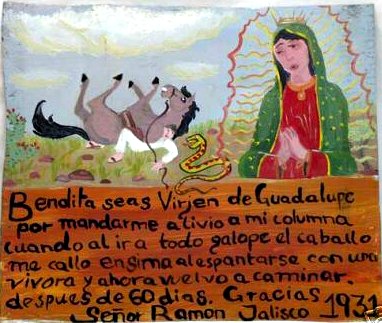

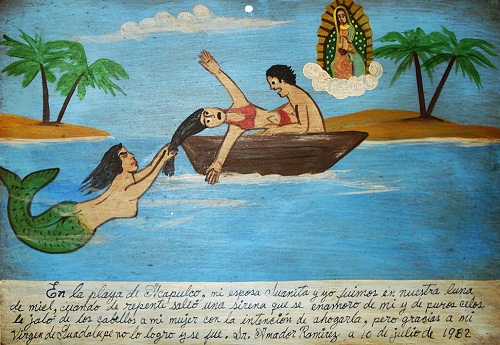

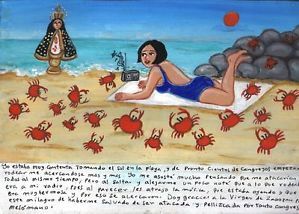

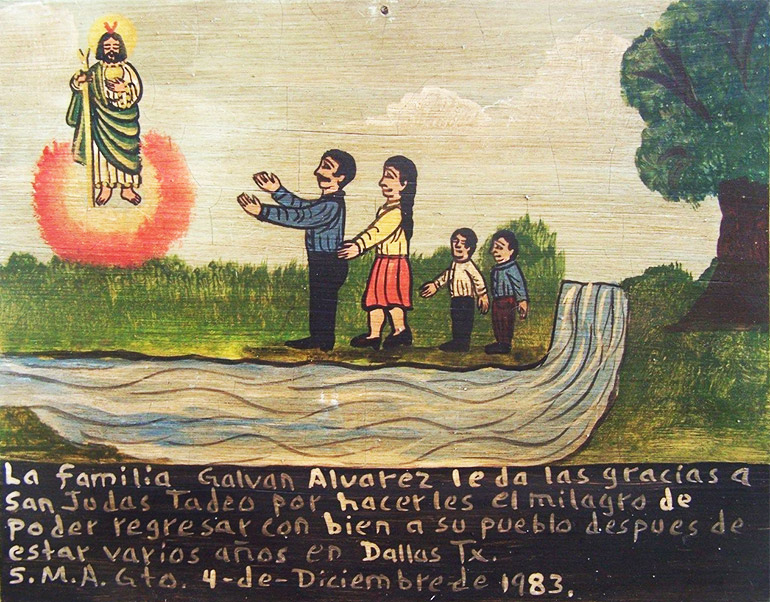

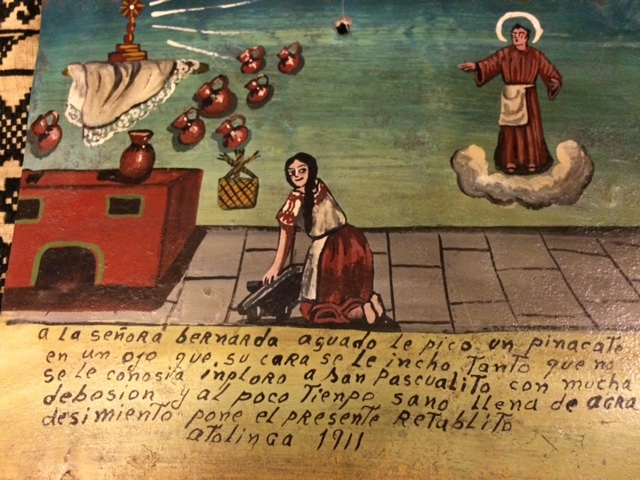

Retablos are Mexican religious art that dates from the early ninetieth through the early twentieth centuries painted in oil on pieces of license plate sized tin. The styles and techniques of retablos are as varied as the anonymous painters.

The greatest number of retablos are from the north central Mexican states, specifically the important religious and economic centers like the farming and mining districts around Zacatecas, fanning north to Durango, and southwest to Guadalajara. From here in Guanajuato then south to Queretaro and north again to San Luis Potosi retablos were made. Thousands have been gathered from these areas by peddlers and antique dealers in the last 30 years alone.

As an anecdotal art form a scene appears in which the victim is in the throes of the situation that has no earthly remedy like surviving flash flooding, falling off a horse or grave illness.

There are three distinct divisions to the retablo. The center section contains the supplicant and often members of the family in the action of kneeling in gratitude for the blessings received. The bottom has the text with the date plus an incident description with the helplessness of the situation. A section at the top or to the side contains an image of the saint of Virgin invoked.

Beside testimonies to faith retablos are peeks into people’s homes. Perhaps not the actually furnishings but a decor that was wished for and painted in a permanent record. It was interior design made to order with framed images on the walls and chamber pots under the bed. Ceilings had beams and floors were tiled. It was the same for clothes featuring the latest in styles despite what one actually wore.

A convert message of retablos, even the recent ones, is the frightening lack of adequate medical attention. People truly had very few options when they became ill. Indeed, it was a miracle that some recovered at all.

Certain saints and themes are overwhelmingly popular in retablos. Marian figures, for example, account for about a third of the images produced. Particularly featured are Mary of Sorrows, Guadalupe and Mary of the Light. Mary’s birth and childhood are rarely represented apart from an association with her mother, Ann. Mary is shown with baby Jesus but never alone with her husband, Joseph.

More male saints are represented because there are more male than female saints.

Some devotions have fallen out of favor and not understood today like devotions for a Good Death or the Lost Souls in Purgatory.

Jesus himself is rarely featured except for his being baptized by his cousin, John the Baptist. Rarely ever did a retablo depict the Crucifixion.

After the revolution of 1920 a movement to establish a national identify through the indigenous cultures gained popularity. This caused a loss of popularity for Spanish inspired retablos here in Mexico and a collection frenzy in the 1950s by US-based art collectors. Among art collecting Mexicans the retablos were considered crude and ordinary.

If a retablo was purchased by a Mexican it was one with an understanding of Mexican art and culture. They were not devotional objects per se. If a retablo was a family keepsake (versus having been placed in a church as an act of gratitude) it was typically included on a family altar. In the US no retablos were used as religious objects though collectors were frequently devoutly Catholic.

If a retablo’s painting has been yellowed from varnish, smoke by candles or faded from touching, it was not necessarily a deterrent to purchasing a piece. Buyers often have a deep understanding of where these objects fit into Mexico’s artist milieu.

Some collectors specialize in specific saints or themes. For example, doctors that collect retablos depicting diseases or folks that preferred retablos with their namesake saint.

Formerly US-based collectors were from New Mexico (in particular Santa Fe), Arizona, Texas and California but the appeal has spread to NYC, Washington DC, Chicago and other urban centers.

Color lithography allowing mass production of religious images caused the rapid demise of retablos, with no apparent consumer loyalty to the product or the artists. Advanced printing technology made images of Virgins and saints more colorful and less expensive than custom ordering a work of art. Today it is difficult to even find a retablo painter, much less afford one.

The attitude of the clergy is also important. Beyond the Basilica to Guadalupe in Mexico City most priests consider retablos clutter. At the shrine to San Juan de los Lagos the storage and display problem is solved by selling the excess retablos to antique dealers.

Whether or not pilgrims and recipients of miracles will continue the tradition is unknown but I still enjoy the present day retablos featured in the local church in Valle de Maiz. Here attitudes of gratitude prevail with saints and Virgins providing modern day miracles with immigration, cyber bulling, traffic issues and credit fraud.

Joseph Toone is the Historical Society’s short-story award winning author of the SMA Secrets book series. All books in the series are Amazon bestsellers in Mexican Travel and Holidays. Toone is SMA’s expert and TripAdvisor’s top ranked historical tour guide telling the stories behind what we do in today’s SMA. Visit HistoryAndCultureWalkin